The Central Asian nation of Kazakhstan is changing its alphabet from Cyrillic script to the Latin-based style favoured by the West. What are the economics of such a change?

By Dene-Hern Chen

The change, announced on a blustery Tuesday morning in mid-February, was small but significant – and it elicited a big response.

“This one is more beautiful!” Asset Kaipiyev exclaims in surprise. The co-founder of a small restaurant in Kazakhstan’s capital Astana, Kaipiyev had just been shown the latest version of the new alphabet, approved by President Nursultan Nazarbayev earlier in the day.

The government signed off on a new alphabet, based on a Latin script instead of Kazakhstan’s current use of Cyrillic, in October. But it has faced vocal criticism from the population – a rare occurrence in this nominally democratic country ruled by Nazarbayev’s iron fist for almost three decades.

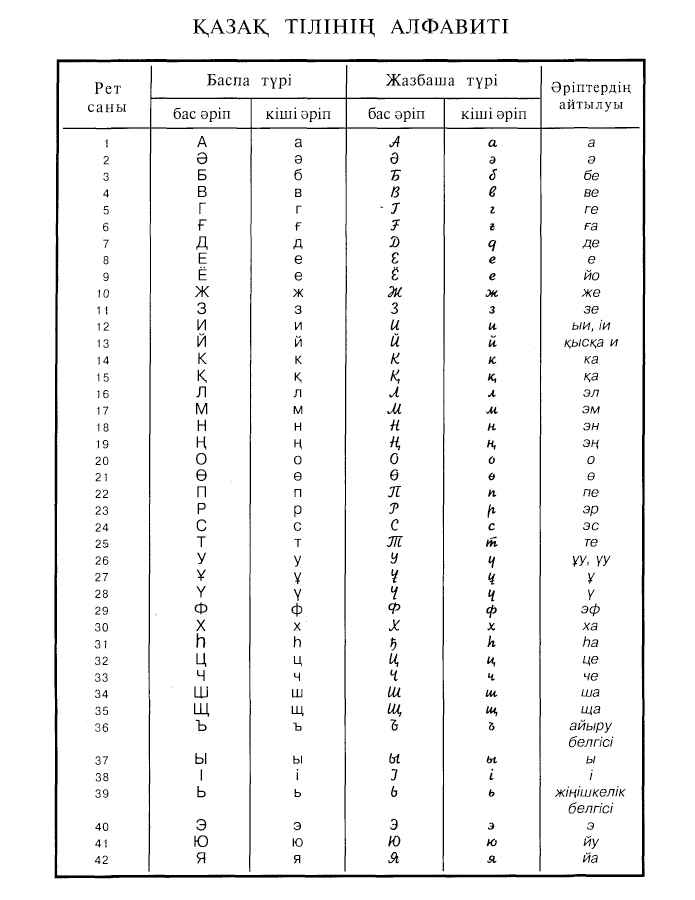

Pinch and zoom on mobile to expand.

In this first version of the new alphabet,apostrophes were used to depict sounds specific to the Kazakh tongue, prompting critics to call it “ugly”.

The second variation, which Kaipiyev liked better, makes use of acute accents above the extra letters. So, for example, the Republic of Kazakhstan, which would in the first version have been Qazaqstan Respy’bli’kasy, is now Qazaqstan Respýblıkasy, removing the apostrophes.

You might also like:

– A ‘thrilling’ mission to get the Swedish to change overnight

“It is more beautiful than the former variant,” says Kaipiyev. “I don’t like the old one because it looks like a tadpole.”

Then it hit him. His restaurant, which opened in December, is called Sa’biz –spelt using the first version of the alphabet. All his marketing materials, the labelling on napkin holders and menus, and even the massive sign outside the building will have to be replaced.

In his attempt to get ahead by launching in the new alphabet, Kaipiyev had not predicted that the government would revise it. He thinks it will cost about $3,000 to change the spelling of the name on everything to the new version, Sábiz.

What Kaipiyev and other small business owners are going through will be happening at a larger scale as the government aims to transition fully to the Latin-based script by 2025. It’s an ambitious goal in a nation where the majority of the population are more fluent in Russian than in Kazakh.

Asset Kaipiyev, co-founder of Sa’biz, changed the spelling of his restaurant – now he has to change it again (Credit: Taylor Weidman)

Mother tongue

According to the 2016 census, ethnic Kazakhs make up about two-thirds of the population, while ethnic Russians are about 20%. But years under Soviet rule mean Russian is spoken by nearly everyone in country – roughly 94% of the more than 18 million citizens are fluent in it. Kazakh fluency is at second place, at 74%.

Years under Soviet rule mean Russian is spoken by nearly everyone in country – roughly 94% of the population is fluent in it

Frequency of usage depends on the environment. In the Russian-influenced northern provinces and city centres, like Almaty and the capital Astana, Russian is used both on the street and in state offices. But in the south and west, Kazakh is more regularly used.

That the Kazakh language is currently written in Cyrillic – and the persistent use of Russian in elite circles – is a legacy of the Soviet Union’s rule, one that some of its neighbouring countries sought to shed right after the union’s collapse in 1991. Azerbaijan, for example, started introducing textbooks in Latin script the next year, while Turkmenistan followed suit in 1993. Kazakhstan is making the transition almost three decades on, in a different economic environment that makes the costs hard to predict.

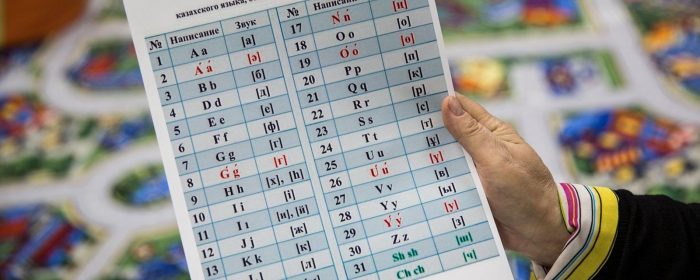

Pinch and zoom on mobile to expand.

The cost of change

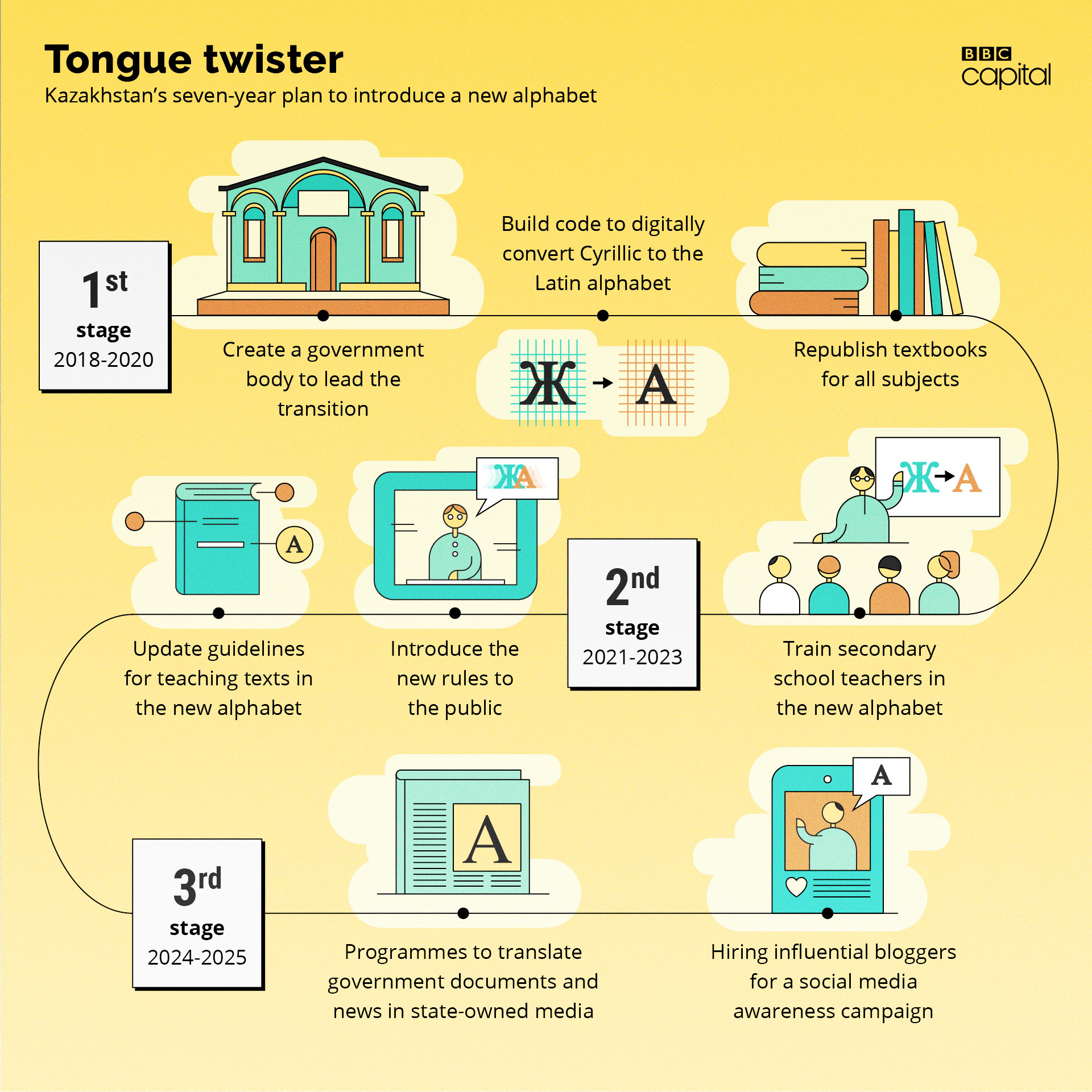

So far, state media has reported that the government’s total budget for the seven-year transition – which has been divided into three stages – will amount to roughly 218 billion tenge ($664m). About 90% of that amount is going to education programmes the publication of textbooks for education programmes in the new Latin script, including for literature classes.

According to state news media, the government has allocated roughly 300 million tenge each ($922,000) for 2018 and 2019; this money will go towards education in primary and secondary schools, says Eldar Madumarov, an economist and professor at KIMEP University in Almaty.

The government’s total budget for the seven-year transition will amount to roughly 218 billion tenge, or $664 million

Meanwhile, the translation of teaching kits and textbooks will begin this year, according to state media, while teachers nationwide will start teaching pre-school and first grade students the new alphabet in 2020, adding a grade each year until 2025, when all levels from pre-school to the final grade will have fully transitioned.

There is also budget for developing a language converter IT program to recode Cyrillic script into Latin in the third quarter of 2018 (approximately $166,000), improving the qualifications of secondary school teachers ($33.2m), and hiring influential bloggers to push forward an awareness campaign for the final stage of the transition, beginning in 2024 ($1.4 million).

But without a clear breakdown provided by the government, some economists have found it difficult to properly assess the direct costs of this massive undertaking. (The ministries of foreign affairs, education, and culture did not respond to requests for comment and clarification.)

Hidden costs

The piecemeal reporting of how the transition will happen makes one economist worried about the unexpected costs.

“If this reform is not properly implemented, the risks are high that highly qualified people from the Russian-speaking majority, which includes also ethnic Kazakhs, may want to consider emigration,” says Madumarov. “The risks may be that some of their opportunities would be cut.”

If this reform is not properly implemented, highly qualified people from the Russian-speaking majority may want to consider emigration – Eldar Madumarov

In late February, the extent of the issue was on display when Nazarbayev – who is comfortably bilingual – ordered that all cabinet meetings be held in Kazakh. Since Russian has long been the lingua franca of state affairs, government officials’ command of Russian often surpasses their Kazakh. One meeting was broadcast over TV, and it showed officials struggling to express themselves. Some even opted to wear translation headsets.

City librarians take a class on the new alphabet at the National Library in Astana, Kazakhstan, on 21 February 2018 (Credit: Taylor Weidman)

Bureaucratic characters

There’s also the cost of changing the language of government affairs. IDs, passports, printed laws and regulations – all the paperwork that governments need in order to function will have to be translated. While this has been reportedly part of the second and final stage of the transition, there has been no listed amount for this expense, says Kassymkhan Kapparov, director of the Almaty-based Bureau for Economic Research of Kazakhstan.

For things like passports and IDs, there is already a fixed fee to renew, “so the only thing that would change is that the letters would just change in the software,” Kapparov says, adding that a new passport costs roughly $60 while an ID card is about $1.50. “The government left it blank. I think the logic is that it would not cost anything.”

But he remains most curious about the third stage, which reportedly begins in 2024 and includes the translation of internal business documents within the central and local state bodies, while state media would also need to implement the new alphabet.

“For the state’s own media to use the new alphabet, you have to train people first of all, then you have to change all the IT infrastructure to embed this script. And then you have to change all the planks [signboards] and the letterheads and stamps and signs,” he says. “For that, they didn’t provide the estimate… based on my estimates, it would be somewhere between 15 to 30 million [dollars].”

That number is only for the public sector, though. “For the private sector, of course they would have to do it themselves. It could be double, it could be ten times,” Kapparov says. “It depends on how hard the government goes about it, like would they require it to change in a single year? It’s possible. With our government, you never know.”

It will cost about $3,000 for Sa’biz restaurant to change the spelling of its name the new version, Sábiz (Credit: Taylor Weidman)

Kapparov also worries that people, especially the older generation, would struggle to read and write in the new Latin script, so communications within the public sector may have to be in several languages at once.

“You can call it the language burden, because when you write a letter inside the public sector, you would have to write it in Russian, in Kazakh, and in Kazakh in the new script… and for that you would need to employ translators,” he says. “This creates additional costs and additional inefficiencies and of course the government doesn’t show it in their budget. But it will create an additional burden on the government.”

When it comes to direct costs, Kapparov is confident that his estimates – which he did in 2007 after the first feasibility study came out and again in January of this year when budgetary information started trickling out via state media – would not be more than $1bn for the entire transition.

But the director of Kazakhstan’s Centre for Macroeconomic Research, Olzhas Khudaibergenov, believes the whole transition will cost far less than Kapparov’s estimate. He thinks all paper documents costs will just be folded into the government’s usual budget. “Real expenses will be only for informational and explanatory programmes to support the transition.

“I estimate that the annual budget will not exceed two to three billion tenge [$6.1m-$9.2m] within 2018 to 2025.”

Economic benefits?

Kapparov says this alphabet transition is “hard to sell” for the government, and there won’t be a direct return on investment.

The alphabet change should be seen as more of a social and cultural development programme – Kassymkhan Kapparov

Rather, it “should be seen as more of a social and cultural development programme of the government,” he says.

Khudaibergenov agrees. “It is more a question of national identity which we are trying to find, and are ready to pay for that.”

KIMEP University professor Madumarov believes the economy could be slowed by political ramifications of the language change. While some have speculated that Nazarbayev’s decision to switch might signal cooling ties with Russia, the gradual shift to a Latin-script language could also weaken trade relations with post-Soviet countries.

Currently, up to 10% of the current trade flow between Russia, Kazakhstan and Ukraine can be explained by the convenience of a shared language, which in some ways translates to a shared culture and mentality, says Madumarov. This also means that Russian-speaking Kazakhs have more economic mobility between countries. Meanwhile, Azerbaijan and Georgia, nations that are not as fluent in Russian, have weaker trade links.

Russian is the language of choice in Kazakhstan’s cities, such as the capital Astana (Credit: Taylor Weidman)

Inversely, he says that the benefits to having a Latin-script alphabet means being better integrated with most of the Western world. As an example, Turkey, which switched to a Latin-based alphabet from its former Arabic script in 1928, has managed to form alliances with the European Union and was in negotiations – up until recently, when the government moved towards a more autocratic direction – to be a member.

Turkey has long been used as an example of how modernisation of the language and legal systems led to its position today as an economic power, says Barbara Kellner-Heinkele, a Berlin-based expert in Turkic languages and Turkic history. But she says this progress is due more to growing literacy and republic founder Ataturk’s firm grip over every aspect of society.

Turkey’s 1928 switch to a Latin script “was done in no time”, but back then, few Turks could read and write: Ataturk needed educated people for his country to be on the same level as Europe and the US, “and part of the education drive was the new alphabet”, she says.

An independent nation

Kazakhstan’s transition is more about setting itself apart from its Soviet past than literacy or economics, Kellner-Heinkele says. “It is a political argument to show that they are an independent state and they are modern and they are a nation.”

Fazylzhanova Muratkyzy, a linguist who worked with the government to create the new alphabet, echoes this assessment, and says many Kazakhs associate the Cyrillic-based script to Soviet control.

Young people, especially, are welcoming the change.

Based on surveys that her linguistic institute have conducted over the last decade, Muratkyzy says that 47% of the younger generation – aged 18 to 25 – supported a switch to a Latin-based script in 2007; that number jumped to 80% in 2016.

47% of the younger generation supported a switch to a Latin-based script in 2007; that number jumped to 80% in 2016

“It is the choice of the people, of the nation. And with this new alphabet, it is connected to our dreams and our future,” she says. “It shows that our independent history is finally beginning.”

Head of national academics Munalbayeva Daurenbekovna discusses the new alphabet at the National Library in Astana (Credit: Taylor Weidman)

Munalbayeva Daurenbekovna, head of the National Academic Library, has been holding open classes for librarians and other interested parties to help them get used to the Latin script. She is optimistic the that young people especially will have no trouble learning the new script.

“Teachers would have to learn every day for one month. For children, it would only take 10 lessons, because children learn faster than adults.”

For Kaipiyev, the owner of Sa’biz, moving away from the Cyrillic script – no matter how tedious it is for him as a small business owner – is something he fully supports. “We want to connect with Europe and America, and with other foreign countries. This will help us turn the page to the next chapter,” he says.

As for changing his restaurant material to reflect the latest version of the alphabet?

“I think I will leave it the same for now,” Kaipiyev says, after a moment’s consideration. “We will change it when the people can actually read it.”

Additional reporting by Makhabbat Kozhabergenova. Additional research by Miriam Quick.

source:

BBC